History

This small town of a little over one thousand inhabitants is situated on the sandy spit between Monte Corpiño to the north and Monte O Enfesto to the south, in the narrow peninsula that ends at Punta A Barca.

The origins of the town go back to the nearby monastery of San Xulián de Moraime. The name of the town (Muxía means “land of monks”) is in fact a reference to the monastery, which played an important role in evangelising the surrounding area.

The first historical reference to the town was in the 12th century, when it is mentioned as part of the parish of Santa María. In 1346, king Alfonso IX granted the town the statutory rights of A Coruña, which gave the residents certain privileges, with the proviso that they should respect the rights that the monastery of Moraime possessed over the town.

Cardinal J. del Hoyo comments in his memoirs that fishing was the only economic activity in Muxía and the town’s jurisdictional space was so small that the locals depended on the parish of Moraime for basic necessities like firewood, water and farm produce.

According to Del Hoyo, the emperor Charles V took Muxía away from the monks of Maraime and gave them another port, and then granted it to the archbishop of Santiago.

According to the Catastro de Ensenada (a regional census), the town had 94 residents (about 350 inhabitants) in the mid-18th century, most of whom worked in the sardine and conger fishing trade. Lace working was an important local craft, partly because of the number of women who worked in the trade and because of the many families who sold it.

The town’s economy in the 19th century was still closely linked to fishing and maritime trade. Lace working and conger drying were also important sources of income. In the mid-19th century, Muxía was a centre of business and services for the municipal parishes. The town also had taverns, ironmongers, lace shops, a doctor, a pharmacist and a lawyer.

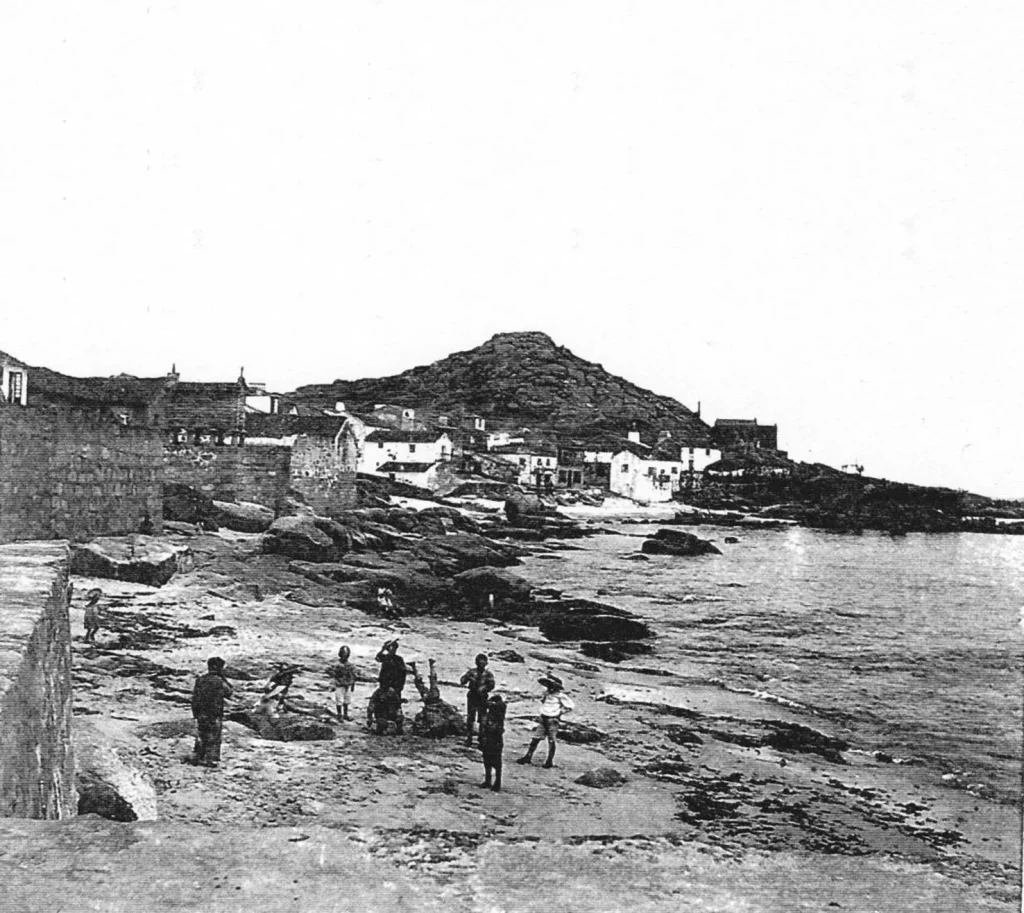

The population had increased to almost one thousand by the early 20th century, and the houses, built of local granite and ceramic tiles,showed a remarkable harmony.

The use of engine-driven boats in the late 1920s was a major boost for the fishing sector. The vast majority of the families in the town lived from the fishing industry, but there were others who made a living in business and other occupations. They formed a small enlightened bourgeoisie that met at the local casino. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War led to deep social divisions and an economic crisis that continued to the end of the 1950s.

Commercial fishing started to undergo an economic revival in the 1960s and the discovery of the O Canto fishing grounds at the end of the decade led to a major increase in the incomes of many families working in the industry. A lot of the money made from the sector was spent on construction that was carried out without any appropriate planning and led to a major change in the town’s image. The construction of the seawall, jetty, promenade and sports marina has also totally changed the old port.

The crisis in the fishing sector that commenced in the 1990s up to the present day meant that many jobs were lost. Tourists attracted by the rich cultural and historical heritage of the region and the promotion of the Way of St James, are creating jobs, albeit seasonal ones, but the fishing industry needs to be revived, given that it is an excellent complement to tourism.

Route on foot around the Muxía peninsula

Muxía is located on a peninsula, which means you can walk all around the edge of the town next to the sea and enjoy the wonderful views over the ría, Cabo Vilán and the Punta de A Buítra.

We recommend starting this route at the viewing point of A Cruz, whose name comes from the calvary that marks the border between the parishes of Muxía and Moraime. It is also gives its name to the beach at the entrance to the town.

If you look eastwards, you’ll see the beaches of A Cruz and O Espiñeirido. The first one is ideal for people coming in from the road to Berdoias, while the second welcomes pilgrims ending the route from Hospital de Logoso to Muxía. If you look to the north west you’ll have a good view of the port and the frontage of the town that overlooks the ría.

The next stage is to walk along the promenade to the monument of the local poet Gonzalo López Abente (1878-1963), who was related to Eduardo Pondal. This monument was designed and made by Andrés Barbazán, an artist from Negreira. The sculpture was commissioned in 1971 to celebrate the fact that the Galician Literature Day was dedicated to the writer.

Continue along the promenade until you reach the jetty of Don Manolo, a small quay built by the local businessman Manuel Lastres to moor his maritime transport vessels. You’ll see an old cannon from the defensive bulwark in A Gurita that is now used as a bollard.

Pass in front of the modern Town Hall, and continue along Rúa da Marina until you reach the Rambleta. The building on the corner where the bar “A Marina” is now used to be a house where the poet Rosalía de Castro stayed when she came to the Romaría da Barca in 1853, accompanied by Eduarda Pondal, sister of the famous poet of Ponteceso. Her time here inspired her to write a poem about the pilgrimage and the novel La hija del mar.

Now you go up towards the Rúa Real until you reach the Praza da Constitución, which is the centre of the old town where the market and fiestas are held. The old Town Hall used to be located here, in the new building that still has some stone columns on the ground floor.

There is a group of restored houses near the plaza that show what the traditional homes of the town were like. Opposite is the recently restored house that was home to the writer Gonzalo López Abente. Keep straight ahead till you reach the next plaza. You’ll see a coat of arms on the gable of a stone house that shows the same symbols as the ones on the house of Pazos de Senande, which suggests that this noble family had a house in Muxía. There is another house in the same plaza with a very worn coat of arms that belonged to the noble family of Dios y Castro. The building where the Casa del Mar now stands used to be the old salt store. The monopoly to sell salt was granted to Muxía in the 15th c. A few metres further on you’ll see another group of restored houses, one of which is the municipal library and the other, the tourist information office.

If you go towards the sanctuary of A Barca, walk as far as the cemetery and then head up to the parish church of Santa María, built in the Marine Gothic style with Romanesque touches. It consists of just one nave with a wooded roof and a rectangular apse with a pointed domed ceiling. The chapel of Rosario (Our Lady of the Rosary), with a cross ribbed vault, can be seen in the north wall. The bell tower rises over some rocks at the foot of the church. Go back to the promenade next to the sea. Look right and you’ll see a structure made of wooden trunks. These are the racks used to dry conger in the open air. There were several conger-drying businesses in this area, which sold the dried fish to the Spanish interior. Carry on walking along the promenade and you’ll come to some magnificent views of the northern coast of the ría of Camariñas, the chapel of A Virxe do Monte and the Vilán lighthouse.

Now you’re at the chapel of A Virxe da Barca, which was built in 1719 with funds from the count of Frigiliana and his descendants, the counts of Maceda. The building itself is Baroque, robust and sober. The interior used to house a valuable Baroque altarpiece by a sculptor from Santiago, Miguel de Romay, which was destroyed in a fire on 25 December 2013.

The famous pilgrimage held to honour the Virgin takes place on the second weekend of September, except when the date on the Sunday is the 8th, in which case it is transferred to the third weekend.

Head down the atrium stairs and you’ll see the legendary stones of Abalar and Os Cadrís, which were Christianised and then went on to form part of the legend of the vessel that transported the Virgin to this place. Rocking A Pedra de Abalar (literally, “the rocking stone”) and passing nine times under the stone of Os Cadrís (literally, “the hip region”) is a popular ritual amongst pilgrims and visitors.

Return from A Barca along the track of A Pel, and at the top you’ll see a huge granite stone: the sculpture of A Ferida, which commemorates the tragedy of the Prestige. From here you can take the track that goes up to Monte Corpiño, the best viewing point of Muxía.

Go back and take the track of A Pel, where you’ll get some beautiful views of the ocean and the headlands of O Cachelmo and A Buítra. A curious thing to see on this part of the route are the stone walls surrounding the small market gardens, which are not dissimilar to the walls of houses in ancient hillforts. These walls were built to demarcate the properties and protect the crops from the sea winds and the salt they bring with them. Just before the first houses, there is a track that goes down to Fonte da Pel, a spring where pilgrims washed themselves before continuing on to the sanctuary. Now head back to the track and go down the Rúa Atalaia toward the Coído. The house of the local photographer Ramón Caamaño Bentín (1908-2007) is at no. 12 Rúa Matadero. He was famous for immortalising the landscapes and people of Costa da Morte. The ground floor of the house contains a small museum with some of his photos and personal effects.

Go back now to the Rúa Atalaia, cross the Rúa A Pedriña and you’ll come to the conger drying racks in this area. Walk from here alongside the coast and you’ll arrive at the Praza de O Coído, regarded as the ground zero during the Prestige disaster, which mobilised thousands of volunteers to collaborate in recovering the coastline. A monument was placed here in 2007 to acknowledge their selfless work. To end the route, we recommend a visit to the Permanent Exhibition at the Voluntariado building, made up of a large collection of photographs that graphically illustrate the appalling ecological disaster that took place in November 2002.